Of all of the episodes in the story of the Hubbledays, this is the one I have most looked forward to writing. It has many of the elements of a romantic adventure story: hardship and poverty, far-flung travel, acts of chivalry and blind panic, self-destructive behaviour, a love affair and eventual redemption. In addition, there is even a story about how this story was discovered! To cap it all, the central figure is the sole reason that anybody bearing the surname Hubbleday is here today.

William Robert Hubbleday, my great-great-grandfather was born in the heart of the Black County in Tipton, Dudley on 16 September 1843 but his parents, Robert and Mary, were not from the area. They were both Londoners who had moved to the Midlands sometime in the 1830s.

This 19th Century map is reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Robert and Mary took their family back to the capital soon after their marriage in Wolverhampton in 1847 and lived in Holborn where they had another son, Robert, in 1851. They then moved to Reading but in 1856 were back in London. The family briefly experienced life in Newington Workhouse, Southwark before settling north of the river in Finsbury. Both of the sons learnt their father’s trade of shoemaking but neither devoted their lives to it.

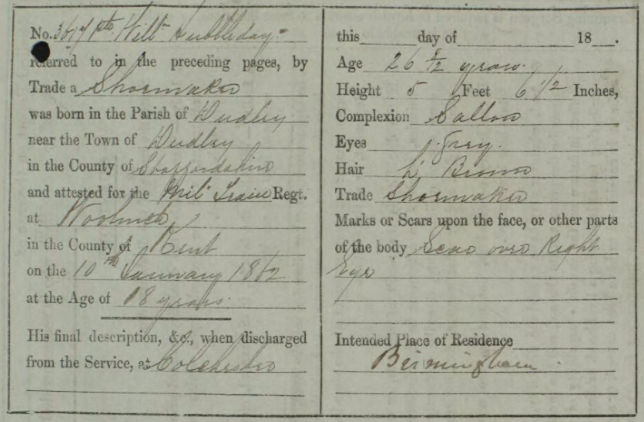

As a young man, William Robert returned briefly to the Midlands. At the time of the 1861 census, when he was 18 years old, he was lodging at the home of a licensed victualler in Horsefair in the centre of Birmingham. His occupation was given as a cordwainer but he was described as a traveller meaning that he was just passing through, presumably looking for work. By the end of the year, he was back in London and on 9 January 1862, he went to the garrison town of Woolwich on the Thames Estuary, and enlisted in the army for a bounty of one pound.

The medical certificate which accompanied the attestation papers gives a few details of William’s appearance. He was 5 feet 5 1/2 inches tall with a sallow complexion, grey eyes, brown hair and a scar over his right eye. This is the earliest description we have of any Hubbleday and the short height is interesting since both my father and grandfather were of similar stature.

The regiment which William joined was called the Military Train and its barracks were in Woolwich in the former Royal Artillery Hospital. It would now be referred to as the Logistics Corps as it was responsible for keeping the front-line regiments supplied with ammunition, tents and food. It had been formed at the end of the Crimean War in 1855 as this conflict had exposed significant weaknesses in the way the army was organised.

William joined the British army at a reasonably quiet time in its history. It was five years since the Indian Mutiny and there was no particular reason to expect a major conflict to develop anywhere in the Empire. Nevertheless, life in the army was not a soft option. Men had to enlist for a minimum term of 12 years and barracks were often overcrowded and insanitary. Flogging remained a standard punishment until it was withdrawn in 1880.

Throughout 1862, unknown to William while he was learning to be a soldier, tensions were rising on the other side of the world in New Zealand. First discovered by Captain Cook in 1769, the two islands had attracted a gradual stream of white settlers from the early 1800s. There had been an outbreak of hostilities in 1845 – 46 as Britain tried to establish its right to rule but, generally, the country had been peaceful. Settlers acquired land from the Maori tribes by buying it rather than through force. The office of the Governor appointed by the British government and many of the missionaries sent out by various church denominations worked hard to see that Maoris were treated fairly. The first Anglican Bishop of New Zealand, George Selwyn, played a particularly influential role in defending the rights of the Maori. In fact, many white settlers came to dislike him intensely because they thought his loyalties were too strongly on the ‘wrong’ side.

By the end of the 1850s, the colonial settlers’ desire for more land than many of the Maori tribes were willing to give up had become a serious concern. Inconclusive fighting broke out in 1860 and was followed by an uneasy truce in 1861. A more serious conflict flared up in July 1863 when British forces moved against the King Movement, consisting of tribes who had united under a single leader in an area called the Waikato about 80 miles south of Auckland on the West coast.

The Colonial Office in London reluctantly agreed to send reinforcements to New Zealand and in November 1863, William Hubbleday found himself on a troopship bound for the other side of the world.

Although there had been ships powered by steam for around thirty years, sail was still the predominant means of propulsion. The Royal Navy had begun adding steam to its wooden sailing ships in the 1840s but even in the 1860s, its new ironclad ships were built with both steam and sails. This was important because they couldn’t rely on being able to refuel with coal while on long journeys. The merchant sailing ship, Empress, which carried William Hubbleday to New Zealand, did not have steam power and would have looked like the clipper in the picture below.

As the Suez Canal wasn’t opened until 1869, the route to New Zealand was down the Atlantic in a south-westwardly direction before swinging East to round the Cape of Good Hope. It was here that the ships picked up the ‘roaring forties’, the strong west winds which blow towards Australia. The journey took a little over three months. A newspaper article in The Sun (London) on 9 November 1863 reported that as well as the Empress having huge supplies of armaments . . . ‘a large number of pigs, sheep and poultry were shipped for the voyage and a patent distilling apparatus will supply 550 gallons of fresh water per day’.

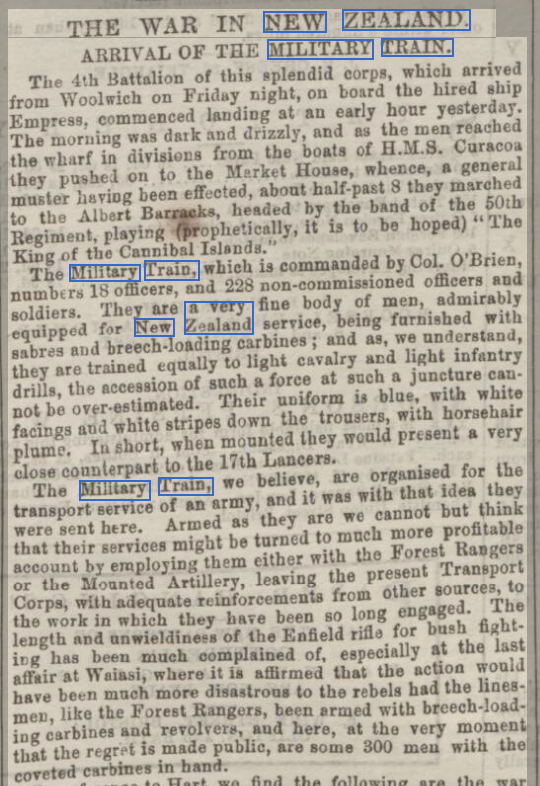

The voyage of William Hubbleday and the 4th Battalion Military Train did not get off to a good start. Within a few days of leaving Woolwich there was a collision with another vessel off Spithead and the Empress and her steam tug Medusa had to put into Portsmouth for repairs. These were quickly completed and the rest of the trip proceeded smoothly. The battalion arrived in Auckland in the middle of February 1864 and the settlers were delighted to see that they were equipped with the latest breech-loading rifles rather than old-fashioned muzzle-loading Enfields still being used by some regiments. It was also noted that, in the absence of any cavalry regiments being sent from Britain, the Military Train might serve this purpose in addition to transporting supplies.

It was decided that a contingent of the Military Train would operate as light cavalry in support of the infantry while the majority of the battalion would carry out their supply role. The personnel for the cavalry troop were rotated so that everyone had their opportunity to see action. William Hubbleday was in the first contingent and served in the field from 18 March to 13 May 1864. It was during this time that two notable engagements took place.

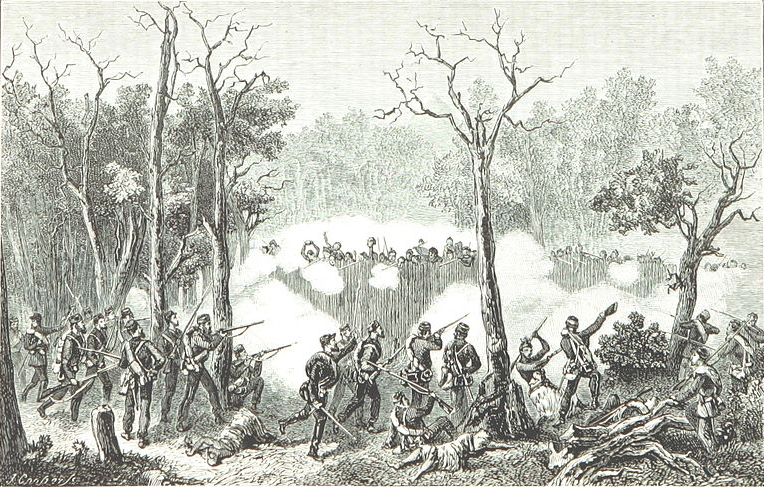

The Maoris employed fast-moving guerrilla tactics and were skilled builders of a defensive fort called a pa which they constructed quickly out of wood and earth. One such pa was at Orakau and at the beginning of April it was defended by 300 Maori, including 20 women and some children, under Chief Rewi. The British and colonial forces who came up against this pa numbered 2,000 and they quickly surrounded it. The Maoris lost their access to water and had little food but withstood fierce attacks and bombardment for two days. On the third day, they were offered surrender terms but refused. Soon afterwards, the British were about to storm the fort when they were stunned to see all of the defenders emerge from a corner of the fort and come running towards them. Sixty managed to clear the British lines and escape but the majority were killed or captured. General Cameron wrote in his dispatches that, ‘It is impossible not to admire the heroic courage and devotion of the natives in defending themselves so long against overwhelming odds.’

The second engagement which took place while William Hubbleday was in the field occurred at another fortress at the end of April. This was Gate Pa on the Eastern side of North island. General Cameron had over 1600 soldiers, sailors and marines at his disposal against 250 Maoris but proceeded very cautiously. The pa was bombarded all day before an attack was ordered. Around half of Cameron’s force was positioned at the rear of the pa while the other half stormed through a breach at the front. The Maoris appeared to be driven back and defeated but their escape route was closed by heavy firing from the troops guarding the rear of the pa. The Maoris turned round and rushed back into the pa causing the British storming party to believe that these were Maori reinforcements. At the same time, Maori who were lying concealed in highly effective anti-artillery bunkers and rifle pits in the pa opened fire, killing most of the officers. Panic ensued and the British soldiers and sailors fled. This was one of the few occasions when British troops ran from an encounter with a native force anywhere in the Empire.

One of the Maori performed a courageous act of chivalry during the battle, which enhanced the respect many soldiers had for their enemy. There is some confusion whether it was a woman or a man but one of the Maoris risked their own life to fetch water for a dying British officer. This story made a strong impression on the Bishop of New Zealand. When he returned to England a few years later, he installed a commemorative stained glass window in the cathedral to which he was newly appointed. This was Lichfield Cathedral and, coincidentally, not far from where William Robert Hubbleday had been born. The Bishop himself is remembered by a memorial in the cathedral which includes a tiled fresco of a scene from New Zealand.

The 4th Battalion of the Military Train remained in New Zealand for several years while the war was played out, occasionally flaring up and then subsiding as the British troops extinguished remaining pockets of resistance. William Robert’s service record shows that he was far from a model soldier at this time. Although he received two good conduct awards in the first three years of being in New Zealand, he started to get into serious trouble at the end of 1866 and for the first half of 1867. He spent considerable lengths of time in the prison cells. Two of his offences are recorded as ‘breaking out of barracks’ and ‘drunk and riotous’, both of which were serious enough to require him to face a court martial. When his battalion left for England on 1 July 1867, he had spent the previous six weeks in the army’s prison. Whether he was simply bored or homesick and had turned to drink, we will never know. He might, perhaps, have been affected by hearing from England that his father had died in 1865 and that his mother and younger sister were destitute.

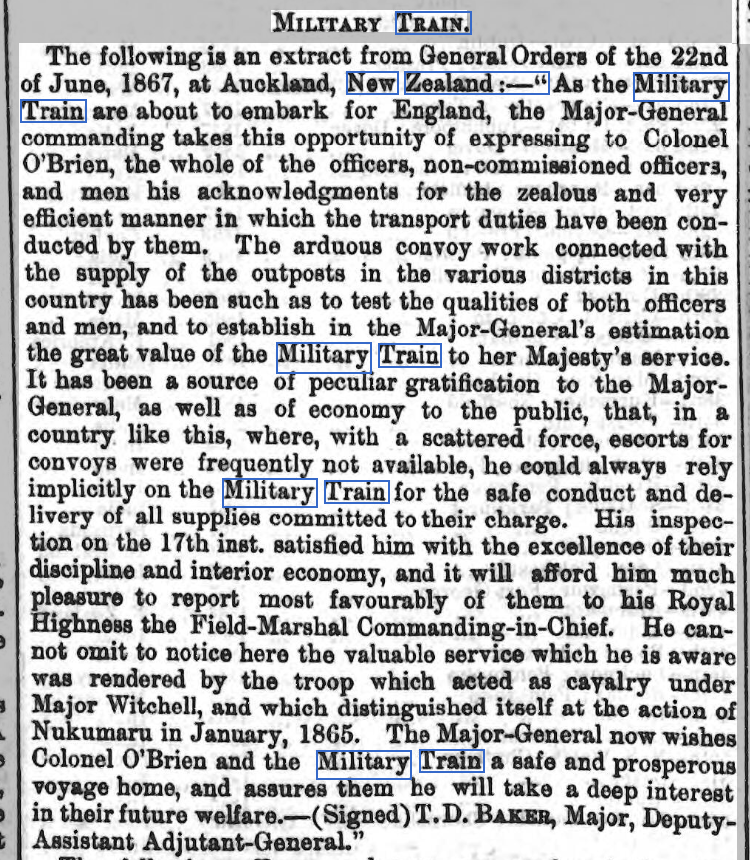

The contribution of the Military Train to the smooth running of the war was widely acknowledged. The battalion won particular praise for a cavalry charge in Nukumaru in 1865 when General Cameron himself had been in danger from an ambush.

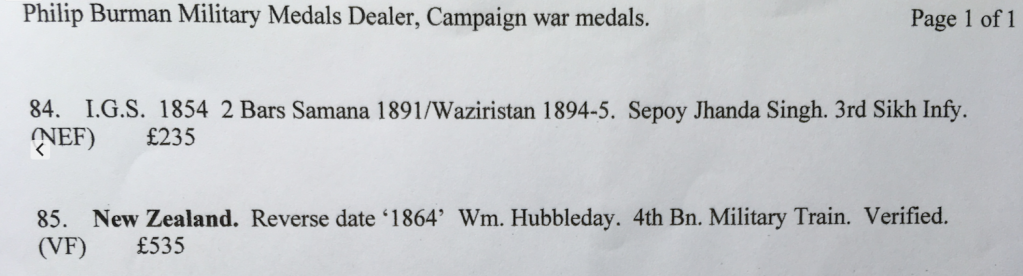

William’s career in the army was totally unknown to me for many years. It was only by a wonderful stroke of luck that I happened to discover that a medal with his name on was being auctioned. One day in 2007, I did a random search on the internet for the name ‘Hubbleday’ and it threw up a listing in the catalogue of Philip Burman, a well-respected dealer in military medals. This was probably the most exciting family history discovery I am ever likely to make. I am pleased to say that I was able to purchase the medal and it is now a treasured family heirloom.

The battalion arrived back in Woolwich on 9 October 1867 and William Hubbleday’s conduct from that point on remained free of any further offences. His sudden unruly behaviour in New Zealand might be explained by what happened within a few months of his return. He married a woman called Mary Ann Dudley, the daughter of a silversmith from Birmingham. Their wedding took place at William Street Weslyan Chapel in Woolwich on 16 February 1868. Although Mary Ann gave her age as 22, she was, in fact, only 19 as she was born in 1849.

Given the speed with which they married, it is almost certain that they had known each other before William’s departure to New Zealand and might even have had an understanding between them. William’s visit to Birmingham in 1861 when he was recorded in the census as ‘a traveller’ may well have been the time when they first met, although she would have been only twelve years old. Mary Ann’s family lived in the parish of St Thomas which is by Bath Row and a short walk from Horesfair where William was lodging.

According to the marriage certificate, Mary Ann was a spinster when she married William. However, the 1871 census shows that she had given birth to a son in 1865 when William Hubbleday had been in New Zealand for 18 months. This news might have reached him at the same time as the news of his father’s death, also in 1865. It is easy to see how the shock of these two pieces of news might have resulted in a great deal of mental agitation when he was so far from home.

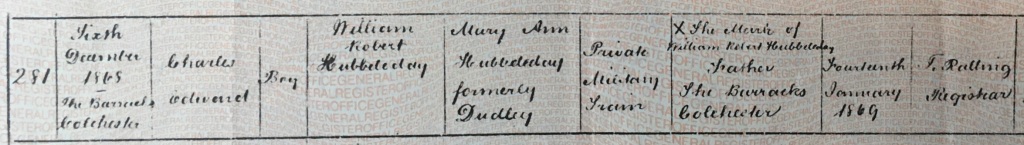

Soon after his marriage, William was attached to the 3rd Dragoon Guards and posted to Colchester, which was an important garrison town. At the beginning of 1869, his wife gave him a son: Charles Edward, my great-grandfather.

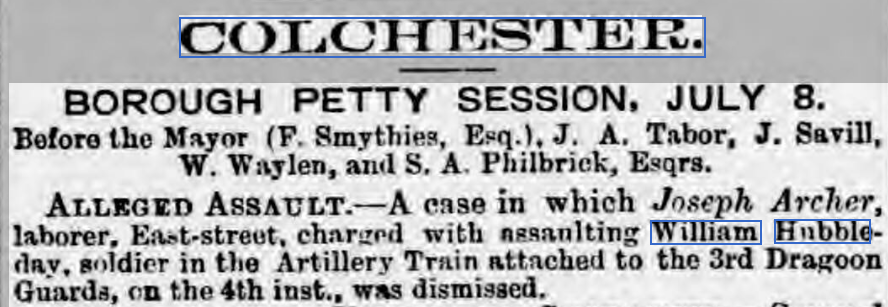

Later that year, William was involved in an altercation with a labourer and the incident was reported in the papers although it appears to have been of little significance.

During 1869, there was a major reorganisation of army supply and transport capabilities and the Military Train was disbanded. Many of its responsibilities were taken over by the Army Service Corps. The changes worked in William’s favour because instead of having to work out the full twelve years of his enlistment, he was discharged early. He left the army on 26 March 1870 after serving just over eight years. His discharge papers show that he had gained an inch in height and that his civilian trade was shoemaking. It was noted that he intended to live in Birmingham, presumably because this was where his wife came from. It was that decision which led to the next five generations of Hubbledays thinking of Birmingham as their natural home.

However, the family didn’t go immediately to Birmingham. At the time of the 1871 census, they were living in Finsbury, North London, which was where he had spent his teenage years. William was working in the London shoemaking trade just as his great-grandfather, also called William, had done a hundred years before. His five-year-old stepson, William, is listed in the census as a ‘scholar’, which meant that he was one of the first children in the country to benefit from the introduction of compulsory education in 1870. This piece of legislation transformed the opportunities available to subsequent generations. However, it took another hundred years before the first generation of Hubbledays were admitted to a university.

William and Mary Ann did eventually move to Birmingham and the story of their lives there will be the subject of another blog. However, there is an interesting story to tell before that one and it also involves a soldier: William’s brother, Robert, the black sheep of the family.

Hello Rob That was great and very interesting, thankyou for sending it to me Regards Graham

________________________________

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome.

LikeLike

Very interesting that we had an ancestor in the military, and who was sent over to New Zealand. Hopefully you can secure a ‘research trip’ over there in the near-future 🙂 And great that you were able to purchase his actual medal from that time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry l haven’t been able to correspond with you ( Canada ) l have been ill, in hospital, nursing homes, etc. I am in a nursing now, just getting settled in. I don’t have a computer, l just use my cellphone.

Thank you for all the research work etc that you have done. Regards! Pamela

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s lovely to hear from you. Your son told me that you had moved but I hoped that you would still be able to pick this blog up if I sent a link to you. Take care.

LikeLike

I’m really pleased you found it interesting, especially as I want you to inherit the medal. I’m afraid that visiting New Zealand any time in the near future looks a distant possibility at the moment.

LikeLike

Excellent article. It is great what you have been able to piece together about your ancestor.

Here’s a description of the Bsttle of Nukumaru from https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/nukumaru-nz-wars-memorial-whanganui

“The battle of Nukumaru was fought during Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron’s west coast campaign of early 1865. Governor George Grey instructed Cameron to first occupy Crown land at Waitōtara, then engage with hostile Māori further north. By late January, a large British force was camped at Alexander’s Farm near Kai Iwi, 15 km north-west of Whanganui.

“On the morning of 24 January, 1000 troops marched north along the coast towards the Waitōtara River. The force comprised men of the Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers, the 18th and 50th Regiments, and cavalry. Although Cameron was in attendance, the force was under the operational command of Major-General Richard Waddy.

Late that afternoon the British force made camp near Lake Paetaia. The site, about 15 km north-west of Kai Iwi and 3 km south-east of present-day Waitōtara, was close to the Māori settlement of Nukumaru, which appeared to be abandoned.

“Waddy set up defensive posts around the camp. While moving to their allotted position, 80 men of the 18th Regiment under Captain Hugh Shaw were fired on from Nukumaru. As the British advanced, the Māori fell back to an established defensive position. Shaw ordered a withdrawal, but returned close to Māori lines with a small party to recover a wounded man. Exchanges of gunfire continued late into the night.

“Four troops were killed in action or died of wounds received during these skirmishes. The dead included Lance-Corporal Patrick Conlin (or Caulin) and Private Patrick Connelly (or Connolly), both of the 2nd Battalion, 18th Foot Regiment. Lieutenant Thomas Johnson (or Johnstone) of the 40th Regiment was one of those who fell ‘mortally wounded’. For his actions, Shaw was awarded the last of the 14 Victoria Crosses won by imperial servicemen during the New Zealand Wars.

“The next day – 25 January – up to 600 Māori crept towards the British position under cover of flax and fern. At 2 p.m. they charged. Two outlying British defensive positions were overrun, with many men killed by pātītī (tomahawk). British cavalry and infantry entered the fray, with hand-to-hand fighting north and west of the camp. The attackers were finally driven off by rounds from two 6-pounder Armstrong guns.

“Thirteen British troops were killed and 32 wounded that day. The British found 10 Māori dead after the engagement, but a later account by a Māori veteran of the battle suggested that 23 Māori were killed. Almost all the bodies recovered – British and Māori – were buried on the battlefield.

“The British force reached the Waingongoro River – nearly 100 km north-west of Whanganui – on 31 March. It advanced no further and, despite having engaged the enemy at Nukumaru and Te Ngaio (13 March), it was regarded by many in political and military circles as a failure. This was Cameron’s last campaign in New Zealand; he left the colony in August.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Roly. Much appreciated. In ‘The Strangest War’ by Graham Holt, 1962, he says that Major Witchell (who I know was commanding the cavalry contingent of the Military Train) warned General Cameron about the positioning of the camp near Nukumaru. Cameron replied: ‘Do you think Major Witchell that any body of natives will dare attack 2,000 of her Majesty’s troops’. Witchell was not happy and ordered his men to keep the saddles on their horses, which proved fortuitous as they were able to mount quickly and charge the attackers.

LikeLike