Occasionally, you strike gold when researching your family history. Recently, I came across a treasure trove of biographical records of soldiers who had died in World War 1. I wasn’t expecting to find anything related to the Hubbledays, but I was wrong.

The incredible power which search engines now possess led me to a photograph of a fallen soldier called Thomas Butt. I was vaguely aware of the name in the family tree but had never gone further than recording him as the husband of Amy Hubbleday. She was my great-grandfather’s sister, in other words my great grandaunt but I had no idea that her husband had ever been a soldier.

The document which revealed his hitherto hidden history is called De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour. It was begun in 1914 by the Marquis de Ruvigny, a British genealogist, who intended to collect biographical details of all those who died in service to their country. The patriotic fervour when war was declared meant that he, like most people, thought that hostilities would soon be over. In the event, his efforts were defeated by the horrific scale of deaths (nearly a million British and Commonwealth military personnel). The project came to an end with the details of just under 26,000 deaths, around 3 per cent of the total. The motivation for the project was set out in the foreword:

Thomas Butt’s entry is on page 44 of Volume 3 of the Roll of Honour. There are 19 men listed on that page: four officers, including one with the Victoria Cross; and 14 other ranks, including a lance-corporal from Birmingham in Thomas’s regiment who had been awarded the Military Medal. Several of the entries contain only the barest details of the man being remembered but Thomas’s is one of the most detailed. As well as precise details about his life, it contains the following words from a comrade: “I can tell you he was one of the best and bravest soldiers we had, and I shall miss him very much, and all of his platoon and myself send you their deepest sympathy.”

Given the small percentage of those killed whose names are recorded, it is remarkable that Thomas Butt made it into the publication. Even more remarkable is that his entry is one of only 7,000 to include a photograph. I am very grateful and moved that Amy Hubbleday or Thomas’s brothers ensured that his life and sacrifice were recorded for posterity. The details in the Roll of Honour have spurred me on to research further into his eventful life as my act of remembrance. Although he was not a Hubbleday, I am pleased and proud to share this story of a brave man.

Thomas’s Early Life

Thomas was born in Aston, Birmingham on 17 December 1880. His father, William Butt, was a carpenter married to Emma Ironmonger, a thimble maker. The couple already had two other children: William born in 1877 and Arthur born in 1879. Tragically, both parents died within a year of each other when the boys were still very young. Their father died of typhoid followed by tuberculosis and their mother from tetanus.

Aged only 4, 6 and 8 the boys were placed in Sir Josiah Mason’s orphanage in Erdington. This institution was an imposing building which catered for 400 children. It had been built by Sir Josiah in the 1860s when he had made a fortune as a manufacturer of steel pen nibs. It seems to have had a good reputation as a school and was known to be strict. For its time, children were treated humanely although teachers gave them numbers rather than using their names. The trust deed gives a flavour of the approach adopted by the school’s management.

Those who are admitted to the Orphanage are to be lodged, clothed, fed, maintained, educated, and brought up gratuitously at the exclusive cost of the Orphanage income. Proper arrangements shall be made by the trustees for the instruction of the children, having due regard to their respective ages and capacities in reading, writing, arithmetic, geography and history. All the children shall be brought up in habits of industry and, as far as possible, the girls be instructed in sewing, baking, cooking, washing, mangling, and in all ordinary household and domestic duties. The children shall be carefully instructed in the knowledge of the Holy Scriptures in the authorised English version.

This detail from a photograph taken by Nicklin, Phyllis (1960) Mason Orphanage, Erdington, Birmingham is reproduced under a Creative Commons licence. http://epapers.bham.ac.uk/623/

Children left the institution when they were 14 and Thomas went to live with his older brothers at 6 Back Lupin Street in Aston. He was there from around 1894, working in one of the many factories in the area, probably as a brass burnisher.

Boer War

In January 1899, Thomas joined the army. His attestation papers show that he signed up with the 5th Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment which was a reserve militia force. He was just under 5 feet 4 inches and weighed 119 pounds (54 kgs or eight and a half stone.) Enlisting in the militia was a well-known way of gaining extra money while continuing to have a civilian job. Recruits were required to do 56 days of initial training and then to attend a training camp for three or four weeks once a year.

However, in May 1900, men in the militia were called up for regular army service as Britain needed to reinforce its troops in South Africa. Thomas was assigned to the 2nd Battalion and a few months later found himself playing an active part in the Boer War. By August 1901, he was entitled to the Queen’s Medal with four clasps indicating the campaigns in which he had taken part: South Africa 1901; Belfast; Cape Colony and Orange Free State.

The regiment’s fighting strength had been greatly reduced by cases of malaria and it was decided to send it to Bermuda to guard Boer prisoners of war. Thomas eventually returned to England in December 1902 and was reposted back to the militia. He had an honourable discharge from the regiment in 1904.

Married Life

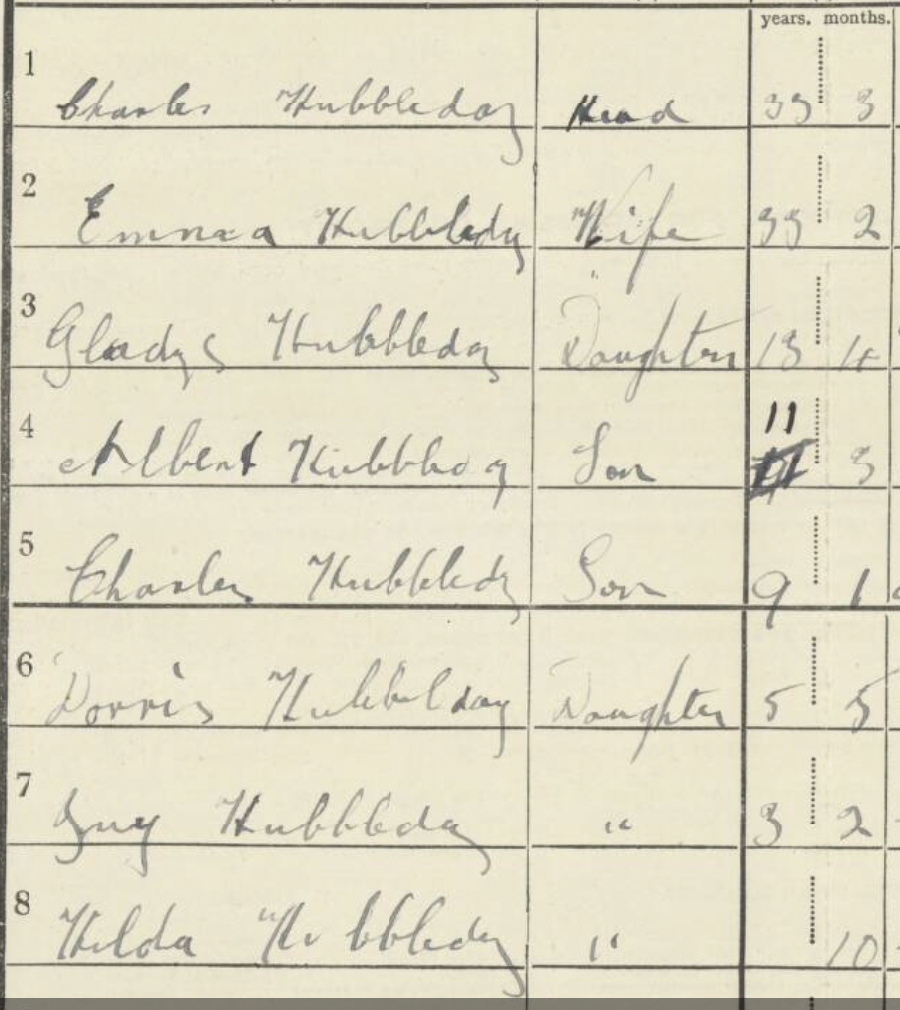

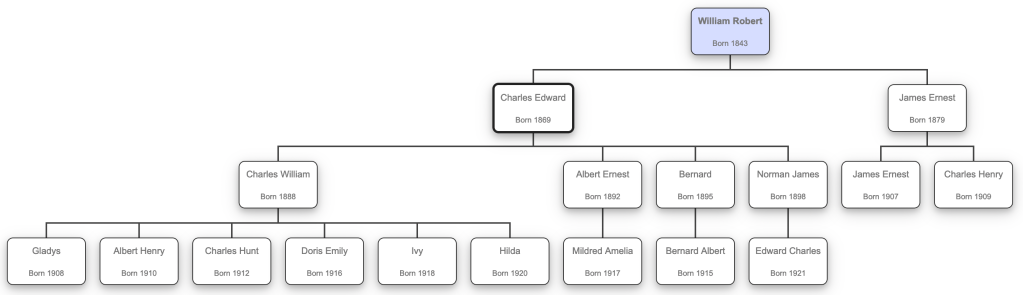

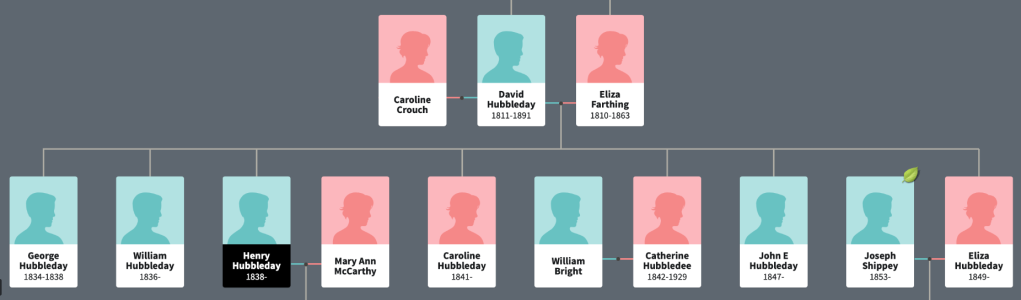

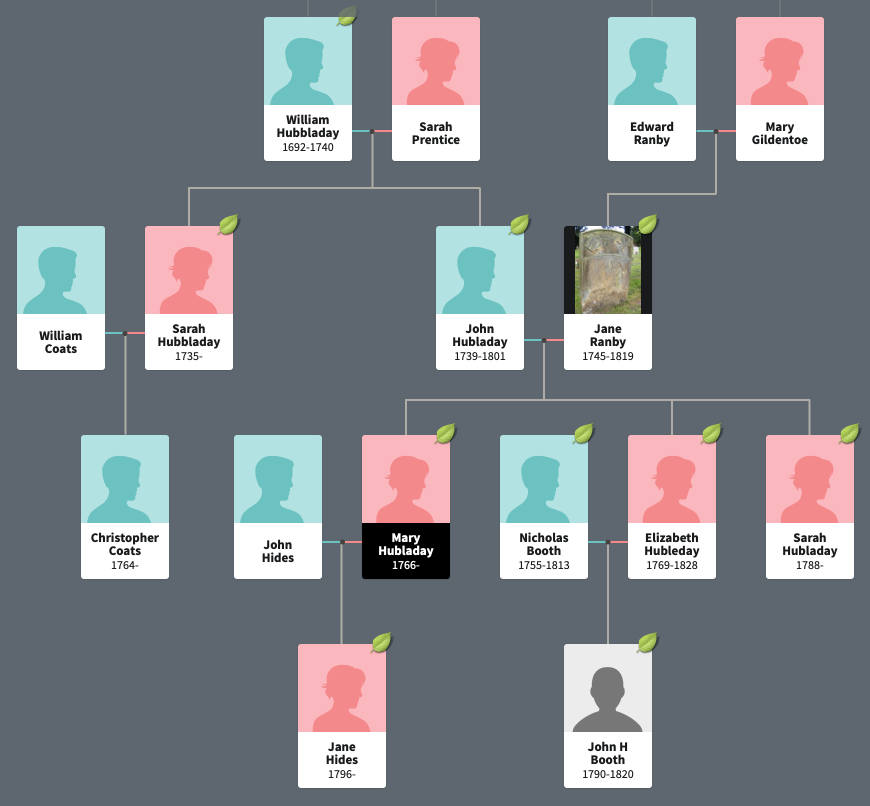

In the same year that he left the army, he married Amy Hubbleday. She had been born in 1884 and was the youngest daughter of nine children raised by William Robert and Mary Ann Hubbleday. William Robert, the Hubbleday from whom all living Hubbledays can trace their descent, had been a soldier in the 1860s but had left the army in 1870 and settled in Birmingham as a bootmaker. After his wife’s death from heart disease in 1893, he had remarried in 1900 to Rose Langston, a domestic servant 15 years his junior.

By the time of the 1901 Census, all of his children apart from Amy had married and left home. Aged 16, she was working as a pin machinist and living with her father and her new stepmother at 6 Ladywood Place. We don’t know where or how Amy and Thomas met but it is possible that they were working in the same factory. For certain, they were both working in the bedstead trade at Reeves & Co in central Birmingham a few years later: he as a brass burnisher and she as a polisher.

Thomas and Amy lived in Alexandra Street, Ladywood and had three children over the next ten years: Thomas in 1907; Edward in 1912 and Florence Beatrice on 25th June1914. Three days after Florence’s birth, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was shot dead in Sarajevo by a Bosnian Serb, triggering war with Germany.

World War 1

Thomas did not enlist again straight away although thousands of other Birmingham men were volunteering at mass recruitment events. Nevertheless, before the year was out, he returned to his old regiment and signed new attestation papers on 17th December, his 34th birthday.

Within a month, he was in France with the 1st Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, part of the British Expeditionary Force trying to counter the German offensive in France and Belgium. By the beginning of 1915, the two armies faced each other in trenches which extended 400 miles across Western Europe. Much of the fighting that year focused on the Ypres Salient, an area of high ground held by the Germans.

The second Battle of Ypres began on 22nd April and Thomas’s battalion received orders to attack on 25th April. They went over the top at 4.30am but were unable to make much headway. By the time the attack was over at 7am, the regiment was at half strength, having lost 17 officers and 500 other ranks killed, wounded or missing. Thomas received a bullet wound in the head and was invalided home from a hospital in Rouen.

The entry in the Battalion’s War Diary for the day that Thomas was seriously wounded.

He recovered and was posted back to France, probably sometime in 1916. Plans were being made for a ‘big push’ in the summer north of the River Somme and the 1st Battalion was being readied for action. Five days of bombardment by British artillery began in the last week of June intended to soften up the German defences. Gas was released by both sides and there were frequent casualties during this period. The Battle of the Somme began on 1st July and 27 men, including Thomas, were wounded during the battalion’s attack on the German lines. This date has gone down as the bloodiest day in British military history as 57,000 men in all were killed or wounded with very little to show for it.

Thomas remained in the regiment and was promoted to lance-corporal. In April 1917, the 1st Battalion was stationed just outside Arras and was once again readying itself to make an attack.

Soldiers attacking near Arras in 1917. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum. Image: IWM (Q 5100)

The Battle of Arras is mostly remembered for the success of the Canadian Divisions in capturing Vimy Ridge. The Royal Warwickshire Regiment had less success in the part they were asked to play a few miles away at Fampoux in the Scarpe Valley. The War Diary for 11th April, the day that Lance-Corporal Thomas Butt was one of 35 men to die, described the first day of action thus:

The enemy shelled our Assembly positions heavily and we had many casualties before starting. The enemy’s M.Gun fire held up our attack almost from the start and the Brigade consolidated a line about 400 yards in front of Assembly position. Both Brigades on our right and on left were held up also by M. Gun fire. Enemy put up a heavy barrage on Assembly positions and vicinity.

So, Thomas was almost certainly killed by shelling before the attack had even started. His name is inscribed on the Arras Memorial at Faubourg-D’Amiens Cemetery. It is one name among 35,000 allied military personnel whose bodies were never recovered from the battleground around Arras.

One of the best-known war poets, Siegfried Sassoon, was wounded in the battle five days after Thomas’s death. He wrote a famous short poem called ‘The General’ which mentions Arras and expressed a common sentiment at the time.

After Thomas’s Death

Amy Hubbleday was able to claim a pension from the government worth 26 shillings and 3 pence a week. An allowance was also provided for children up to the age of 16: ten shillings for the first child, seven shillings and sixpence for the second and six shillings for any further children. A few years after the war, she was sent the medals that her husband was entitled to: the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. The families of soldiers killed in action also received a bronze plaque, popularly known as the ‘dead man’s penny’ because of its similarity in appearance to the much smaller penny coin. It was inscribed around the edge with the words: ‘He died for Freedom and Honour’.

By this time, however, Amy had remarried, forfeiting her widow’s pension. In January 1919, she married Frank Currall, a paving labourer, who was a year younger than herself. She had three young children to care for and although Thomas’s death was honoured by his country, it is quite likely that she may have felt very differently about his sacrifice.

Kendrick Randolph Frank Currall, to give him his full name, had also been a soldier in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. He had joined the 1st Battalion in 1905 and served six years in India and Ceylon. However, his story is less inspiring than Thomas’s. He was discharged with ignominy in 1913 after being sentenced to 56 days’ detention for gross misconduct. More shockingly, before joining the army, he had been sentenced to three years’ imprisonment in 1902 for a serious sexual assault on a girl with a group of other men.

Perhaps Amy didn’t know or perhaps he was a reformed character. Their marriage seems to have lasted as they were still together when the 1939 Census was taken in preparation for another war. Sadly, her son, Edward had died in 1922 aged ten, but the other two children married and lived into their eighties. Amy died in 1955.

I would love to know if Thomas’s story was kept alive in the family. I wonder if his children and those that came after them ever read the memorial in De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour.

The image at the beginning of this blog showing British and German trenches around Arras is reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.’ Map Images website.